Grave Adaptation

IDK what I expected from the new "Great Expectations," but it wasn't this

Teaching a book made it mine in profound and idiosyncratic ways. Some I taught year after year, experiencing them again and again; even those I initially disliked would win me over. My relationship with these books became intertwined with my relationships with my students, who made me understand them more fully. Certain scenes, characters, or themes we focused on in class attached themselves to my memory, while others fell away.

This can create unusual and unfair reactions to film adaptations, so I approached BBC Studios’s new “Great Expectations” determined to receive it as a series “based on” rather than a faithful adaptation and to prepare for the necessary excising of minor characters and paring down of plot.

Two episodes in, that determination has been broken.

Charles Dickens’s “Great Expectations” is often taught as a bildungsroman, the coming of age story of the orphaned Pip. One of the joys of reading it with adolescents was that, though still children, they are older and wiser than Pip when the story begins, and they readily adopt him, empathizing with his plight and delighting in his early naiveté, communicated with wry humor through Pip’s narration.

The series’s young Pip is played by Tom Sweet, who has a face worthy of his name and a name worthy of Dickens. But the character is written with a good deal less innocence and more agency than Dickens gave him. In early scenes, Pip fantasizes about living in London and traveling to the colonies, tells Joe he won’t take over the blacksmith’s shop, and decides (he gets to decide!) that spending time at Miss Havisham’s Satis House will enable him to reach his goals.

When the novel opens, however, Pip is just forming an understanding of his place in the world, only starting to become conscious of selfhood:

My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening. At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.

The original Pip’s world is small, circumscribed by poverty and the hardship it brings; there is no London or beyond. And this is important. Because at Satis House — where he is deposited without having a say — he will learn from Miss Havisham and Estella his place in a world cruelly structured by social class — and become ashamed of the self of which he only recently became aware. In a novel stuffed with incredible caricatures and coincidences, Pip’s realistic vulnerability as a child being buffeted by forces outside of his control resonates with readers of all ages.

The series’s young Pip does not appear governed by fear and guilt and shame. He spends his years at Satis House enduring abuse with soaring ambitions in mind, seeing it as the means to an end. With four episodes to go, it’s not clear why this change was made, but it’s hard to see how Dickens’s social commentary won’t be warped by it. In the novel, Pip exhibits no early desire to explore the world and leave Biddy and Joe behind; it is only exposure to the upper class that leads him to leave them, reject his roots, and abandon his conscience. The early episodes also sideline Joe, giving him more dignity but providing less of a sense of his essential goodness and the deep love between them that makes Pip’s later betrayal so heartbreaking.

The series embraces the Gothic elements of the novel to good cinematic effect: the salt marshes are all gloom and menace and Satis House feels eerily frosty even as the seasons change. But it’s all gloom all the time. Dickens used Gothic conventions to serve his satirical purpose, weaving levity into otherwise creepy moments to highlight absurdities. When Miss Havisham sends Pip into the room where she wishes her corpse to be laid out beside her rotted wedding cake, he notes the spiders coming and going from it “as if some circumstances of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community.”

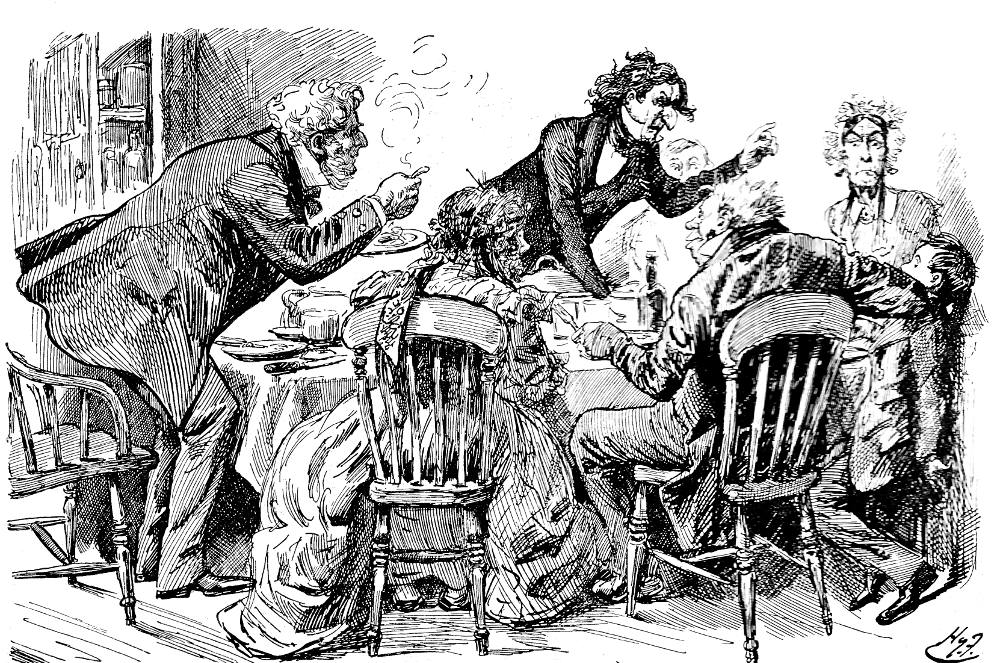

“Great Expectations” is many things, maybe too many things, but it is frequently very funny and not simply as comic relief. At times the humor is warm, but often it is in service of rough and meaningful ridicule. Pumblechook, a pompous blowhard and harmless fool, Dickens’s merchant class “ass,” provides no humor or clear message in the series; instead, he is pointlessly engaged in a disturbing sexual affair with Pip’s sister. Miss Havisham and Estella lay about smoking opium, muddying their motivation. All lightness is drained from this “Great Expectations.” When so much is darkness, it’s harder to make out what is being critiqued and what has been added purely for shock value. Dickens didn’t produce cruelty and shock simply to entertain; he entertained, at least in part, to produce shock over cruelty.

Dickens’s “Great Expectations” is a cacophony of characters and mysterious motivations and outrageous coincidences that no mini-series could fully capture. This series so far, though, is a relentless darkness pointing toward London, and I don’t think I want to follow it there. I’d rather hold onto my memories of the book and how my students embraced, critiqued, and forgave our Pip — and maybe go back to “the old place” and read it one more time.