The Anxiety of Alex Murdaugh

And the danger in mundanity

I just spent a couple of days watching a liar.

Alex Murdaugh, on trial for the murder of his wife and son, testified on his own behalf last week. On the stand, he admitted to being a liar, explaining he had lied repeatedly to police about his presence at the murder scene near the time of the killings. “Once I lied, I continued to lie,” he told the jury — before going on to try to persuade them he wasn’t a murderer.

Because I watch too much “Dateline,” even though I hadn’t been paying attention to the trial until Murdaugh began testifying, I already knew a lot about him: that he stole millions from the family of the housekeeper who died in his home, that he has been charged with numerous other financial crimes, that he has been accused of conspiring to frame someone for his son’s boat crash, that he was involved in a bizarre shooting-for-hire on a deserted road, that he is the scion of an affluent and powerful South Carolina family. Given all this and the horror of the crimes he is now on trial for, his testimony was bound to be fascinating.

Some commenters on social media were disappointed from the outset, complaining Murdaugh was downright boring. This seemed to be exactly his desired effect: appear boring and normal.

Murdaugh Most Mundane

Under questioning by his defense attorney, Murdaugh provided lengthy descriptions of the days and hours leading up to the murders with frequent asides on the habits and traditions of family and friends, painting the picture of a down-home family man. His repeated use of endearing nicknames — Daddy (his father Randolph Murdaugh III), Mags (his wife Maggie), Paw Paw (his son Paul), Ro Ro (a friend named Rogan) — suggested a bland sweetness, even naivete. Details evoked a simple country boy rather than the scandal-swirled scion of a rich and powerful family. He spoke of baseball and tailgating and Krispy Kreme donuts, of trucks and fields and a dog named Bubba.

These detours into the mundane were meant to normalize Alex Murdaugh to the jury. What made it compelling viewing is that his life and behavior have been anything but normal.

Prosecutor Creighton Waters used the first part of his cross-examination to make this clear by establishing a timeline of Murdaugh’s privilege. Murdaugh squirmed hardest when asked to acknowledge his obvious advantages. Born into a prominent (he did not like this word!) family of lawyers and prosecutors with a close relationship with law enforcement, he benefited from intergenerational wealth and power. Key was the opportunity to join the family law firm, where he was able to exploit his position to steal — for many years with impunity — from others less wealthy and less powerful.

Waters hammered on the number and names of clients, colleagues, friends, and family members Murdaugh had lied to, forcing the jury to consider whether anything he said could be believed and further refuting Murdaugh’s presentation as a benign Everyman.

Not Just Spectacle

Some have asked why Alex Murdaugh’s testimony was being streamed live on cable news networks. Whether it was newsworthy enough, I can’t say. I do know that I found it deeply compelling and not merely entertaining in providing a rare view of a man of wealth and privilege being held to account for destructive behavior — maybe.

As tragedy did for the ancients, contemporary true crime, even if it sometimes seems tawdry, provides an opportunity to have our fears stoked and purged. Murdaugh’s case stands out because it taps into so many fears: of lethal violence, of domestic abuse, of betrayal, of being cheated, of being lied to and manipulated, of being misled by power.

Research shows that the audience for shows like “Dateline” skews female, and that women often watch for the comfort of seeing criminals being brought to justice (as they mostly are on these shows) and to learn about the psychology of criminals as a way to learn how to protect themselves from being victimized.

The tension I felt simmering under even the slowest moments of direct and cross-examination was the worry a criminal could go unpunished. After all, Murdaugh is an expert in the law. He appeared indefatigable in his hedging and hawing, redirecting and redefining — the man filibustered so long that the jury might have forgotten why they were there. He is an expert in lying, who probably passed Gladwell’s 10,000 hours just in the cover-up of his other crimes. If he is guilty of double murder, then he is also an expert actor, running the emotional gamut from nostalgic to grieving, penitent to indignant. Mostly though he remained incredibly calm, as though on a routine conference call. Even if he is innocent, the situation required a performance.

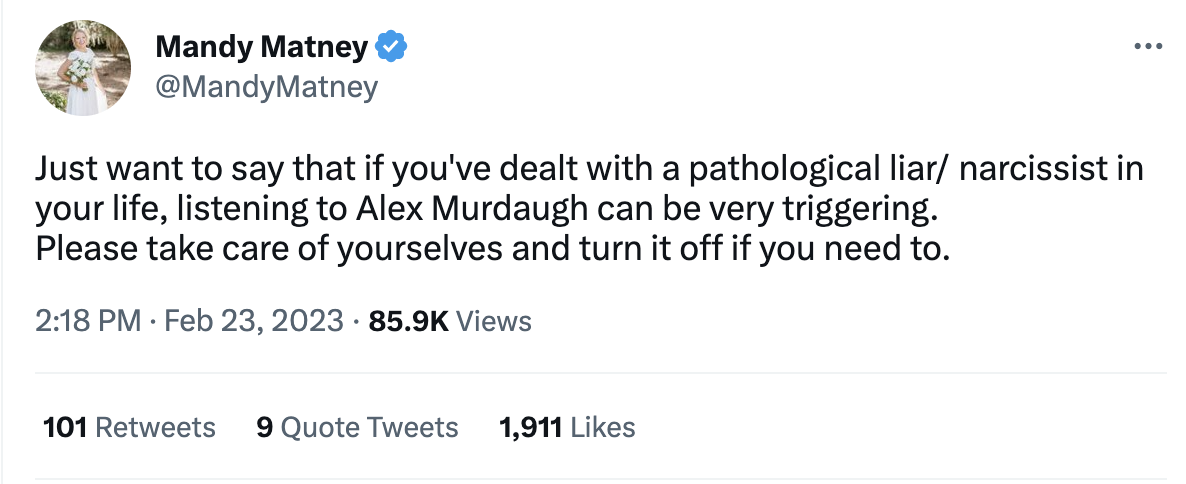

That performance made me deeply anxious. I could see it as false; someone else could see it as genuine. Survivors of manipulation by liars, cheaters, abusers, or thieves were rightly warned that watching it could be a difficult emotional experience. The attempt to normalize a serial criminal is a horror to anyone who has been victimized by people with the power to convince others that they are incapable of doing the harm that they have done to us.

Given Murdaugh’s history, it wasn’t hard for me to believe his lying didn’t end with where he was moments before the murders, so I found it chilling to watch him wax on about his slain wife and son. A history of lying and stealing doesn’t make someone a murderer, but not knowing where someone without a conscience draws the line is one of the ways those people have the power to inspire fear.

Lie Detection Matters

When I taught a suspense literature class, something my students and I discussed was why dramatic irony, a common tool of suspense writers, is satisfying for the reader. The consensus was that knowing (or thinking we know) something that a character does not know creates deep anxiety: We can’t help them avoid the terrible fate we see about to befall them. At the same time, the benefit of some omniscience can make us critical. Why can’t they see what we see?

Watching a jury trial as a lay person, especially when knowing facts the jury may not because they have been deemed inadmissible, can have that same effect. I curse a jury that fails to acquit someone I believe was falsely accused or to convict someone I believe is guilty. I worry this jury will be duped, as I have been duped in the past, or as judges and juries have been influenced in a society where accountability often depends on power.

Just like most people think everyone else on the road is an idiot but they are excellent drivers, we humans think we are good at detecting lies — but we are not. Social scientists have discovered we might do better to toss a coin when trying to figure out if someone is lying. In a study by psychologists Charles F. Bond Jr. and Bella M. DePaulo, people were able to determine that a lie was a lie 47% of the time and determine a truth was a truth 61% of the time; numerous studies have shown similar results. I’m probably no better at this than the average jury. And the average jury isn’t much good at this.

Professor of Social Psychology Aldert Vrij, author of Detecting Lies and Deceit, says that sometimes people fail to detect lies in daily life because “the ostrich effect” causes them to fail to investigate or evaluate it. Sometimes they don’t want to see the lie because acknowledging the truth would be too painful or would mean they would have to do something they don’t want to do, like give up a relationship with the liar. Alex Murdaugh’s living son has stood by his father throughout, even testifying for the defense. He’s a man with a lot to lose.

This research helps explain why politicians get away with lying, even though voters say they value authenticity and honesty. The exposure of a serial fabulist like George Santos produces derision — how can he think anyone believes him at this point? But then Donald Trump was caught lying 30,573 times during his presidency and still has 68% favorability among Republicans. Perhaps Santos thinks if he just keeps showing up every day in a suit, his constituents and colleagues will forget how he got there, just as Murdaugh likely hopes the jury remembers more of his talk about his family’s life on the farm than details of Maggie and Paul’s deaths there. Both might work.

The Murdaugh trial is a reminder of the danger of normalizing the abnormal, ignoring lying, and denying the power of privilege. A prominent man with a fantastic past wants to lull a jury into seeing him as normal and thus harmless. Watching his trial may also have served as a proxy for my larger fears.

Right wing politicians and media have worked to soothe their followers, convincing many that an insurrection was a minor incident, a kerfuffle caused by ordinary people who cosplayed too hard, not part of an attempt to overturn democracy by political elites. A congressperson calls for dissolving the nation and complains about the federal government as though she isn’t one of its most powerful officials, then walks into the Capitol and its daily business. Extremists lie and lie, gambling (to borrow Joyce Vance’s language) that their normalization will disempower those who aren’t true believers or ostriches.

Will the anxiety of the Murdaugh case end in catharsis? As Vance explained, it only takes one juror (she corrected herself in the next tweet) who believes Murdaugh to deny that satisfaction. Then I’ll have to wait for Fani Willis and Jack Smith.