The Good Time of Martin Amis

On the passing of a favorite author

“We read literature to have a good time,” British author Martin Amis told an interviewer a few years ago, “Not an easy time, necessarily, but not a hard time and not a bad time. So I like fiction that makes me welcome, and I’m quickly exasperated by the freakish, the introverted and above all the compulsively obscure.”

I’m not sure that in my 20s, when I was devouring Amis’s novels—less than conventional, often disturbing—I would have described them as welcoming. But when I learned last week that he had died, I recalled my deep pleasure in reading them.

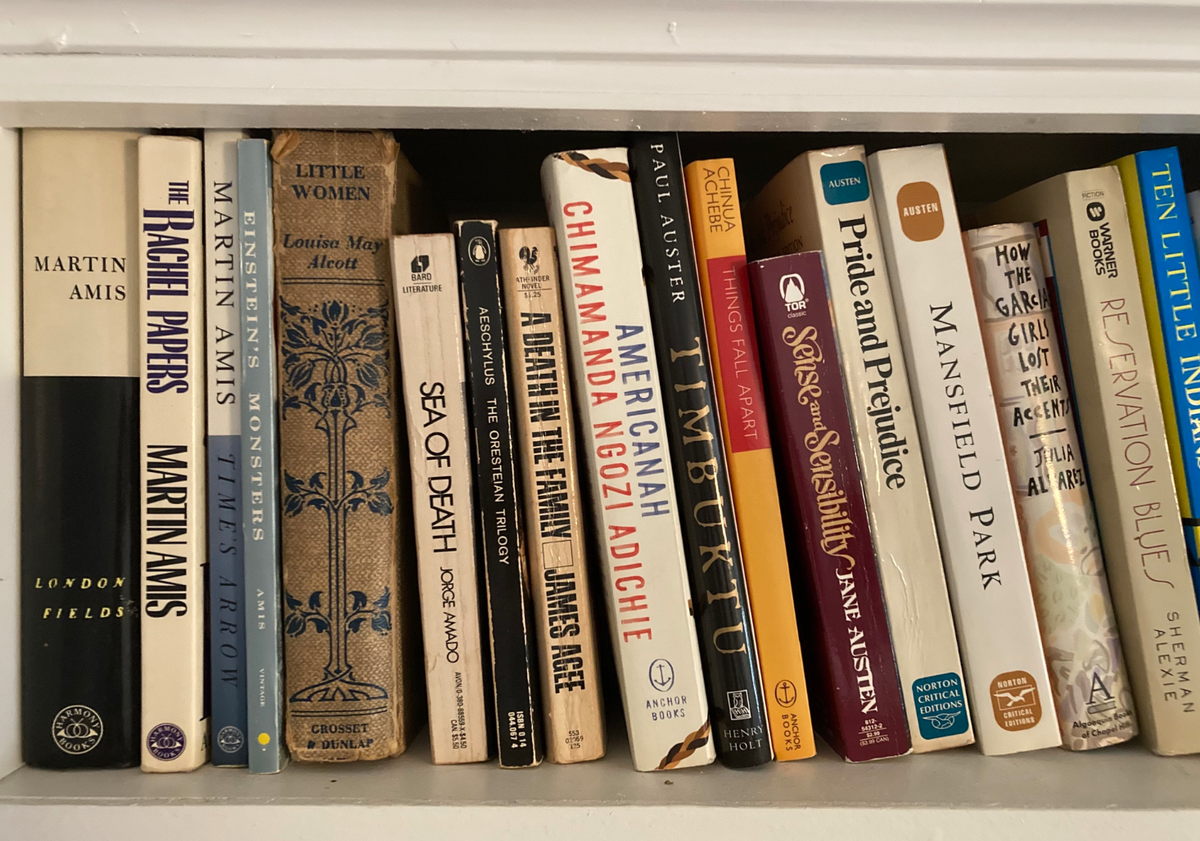

I had just returned from living in London when I saw “London Fields” in a bookstore window. In school, I had been assigned some of the kind of fiction Amis complained about (Coover’s “Pricksongs and Descants” comes first to mind, and I never read a second Faulkner, who Amis uses as an example of a writer who makes reading too much work). But now I was filling my bookshelves to my own taste, spending Saturdays in bookstores browsing, skimming, trying to avoid the “easy,” “hard,” and “bad.” Having been raised in the suburbs, I was exhilarated by cities and wanted stories set in them. New York was the love of my life, but London had been the grand affair, so of course I brought home “London Fields.” Before finishing it, I went back and bought several of Amis’s earlier novels.

In retrospect, “London Fields” did “welcome” me by advertising itself from the first page as a piece of metafiction, a developing obsession that I would foist upon my students when I became a teacher, convinced they could be as excited by, as John Barth put it, a "novel that imitates a novel rather than the real world." Reading Amis in his time as a young writer and mine as a younger reader was “a good time” because he played with perspective and narration — as had and were some writers whose works he eschewed. The novel opens with the line: “This is a true story but I can’t believe it’s really happening.” To this day, I have not tired of fiction about fiction, whether it announces itself up front this way, like the ringing of a phone (Auster’s “City of Glass”) or approaches with more patience and stealth (McEwan’s “Atonement.”)

The opening of “London Fields” is from the point of view of Sam Young, a writer:

This is a true story but I can't believe it's really happening.

It's a murder story, too. I can't believe my luck.

And a love story (I think), of all strange things, so late in the century, so late in the goddamned day.

This is the story of a murder. It hasn't happened yet. But it will. (It had better.) I know the murderer, I know the murderee. I know the time, I know the place. I know the motive (her motive) and I know the means. I know who will be the foil, the fool, the poor foal, also utterly destroyed. I couldn't stop them, I don't think, even if I wanted to. The girl will die. It's what she always wanted. You can't stop people, once they start. You can't stop people, once they start creating.

What a gift. This page is briefly stained by my tears of gratitude. Novelists don't usually have it so good, do they, when something real happens (something unified, dramatic and pretty saleable), and they just write it down?

The opening is more than welcoming; it’s irresistibly tempting. Key to what Amis perhaps meant by “welcoming” the reader is a comprehensible (if complex) and propulsive plot. (Faulkner, he said in the same interview, “isn’t interested in pushing the narrative forward.”) What better genre than a mystery or thriller to keep a reader from begging off early? Mysteries are meant to fool; thrillers are meant to thrill. Both demand manipulating narrative without sacrificing suspense. I’ve forgotten much about “London Fields” and “The Information,” his 1995 novel, but I’ve never lost the feeling of reading them: the excitement and dread in their persistent darkness and escalating menace. Specific characters, specific events are blurred out; they are in someone else’s past. But the atmosphere of these books remains very present. From its high shelf, in its yellowing cover, “London Fields” still calls down that terrible things are going to happen. These are not books to read in the sun. They are not that kind of “good time.”

In an author’s note prefacing “London Fields,” Amis shares that he considered titling it “Time’s Arrow.” He used that title shortly after, for his only novel that I have read more than once. It’s no sort of “good time”—but this is an exceptionally good time to read it.

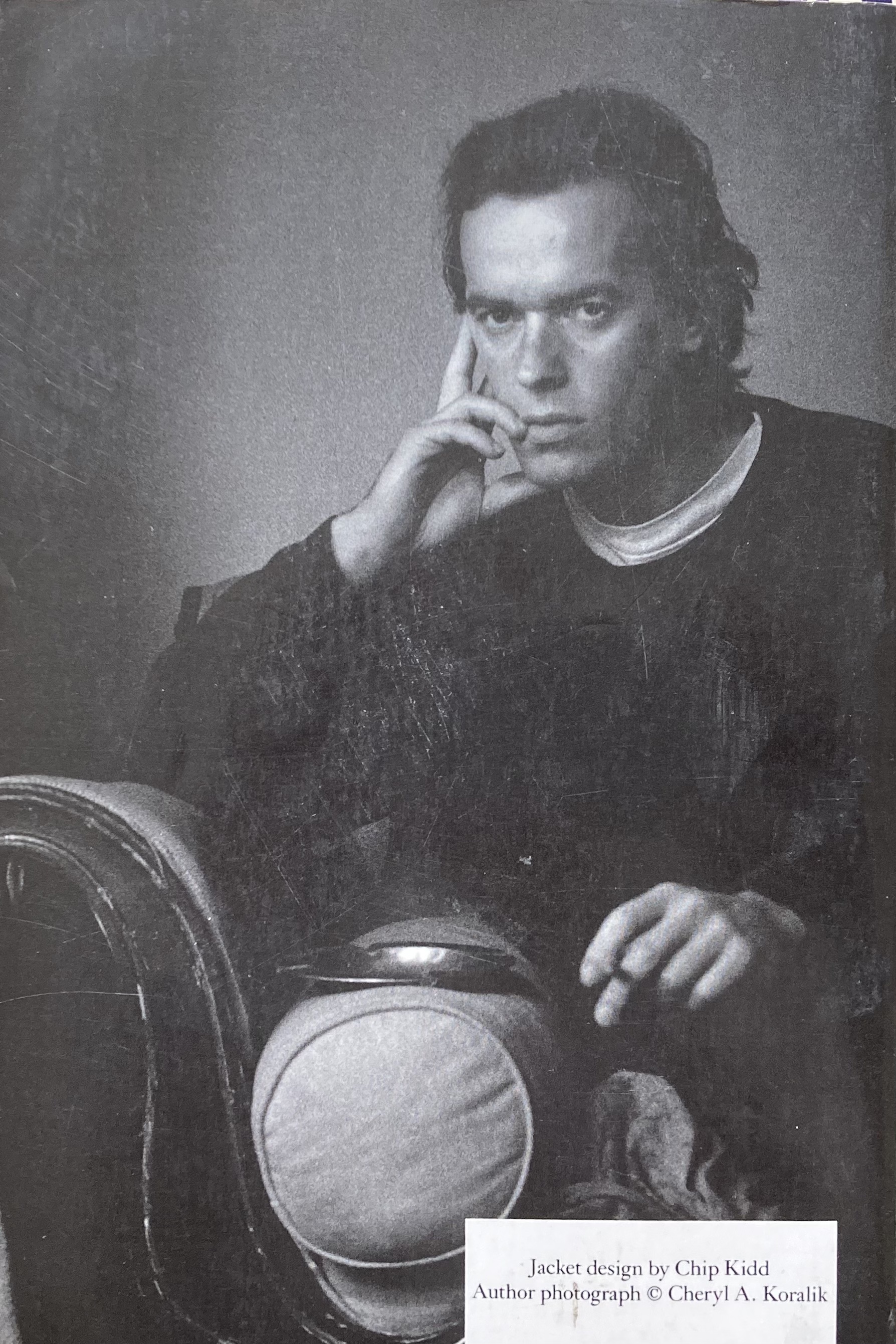

“Time’s Arrow” is written in reverse—a remarkable feat, something that does not seem as though it could be sustained over the course of a novel (or even a novella, which it more properly is), but Amis does it. Not knowing this going in (my copy has no description on the back cover, just a photo of Amis sitting broodingly on a couch) was disorienting; I remained off keel even after I realized the narrative flows upstream, not down, into the past, not the future. The shit comes first, then the morning coffee, then bed. A man and a woman meet, then fight bitterly, then love, then treat each other with increasing distance, until they separate as strangers—the reverse journey of a typical relationship but also the forward journey of a dysfunctional one.

“Time’s Arrow” is an exploration of time, consequences, and the myth of human progress. It also happens to be about fascism, and in the current era, the violent contradictions, perversions, and reversals of fascism that Amis highlights have added resonance.

I haven’t read all of Martin Amis’s books. I have a tendency to read a favorite author until I have sated myself or because I want to save the rest for later. Now it’s later.