The Mid-Life Crisis, But Forever

On “Fleishman” and the trouble with aging

Binge-watching Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s smart series “Fleishman is in Trouble,” in which a friend-group of affluent Elder Millennials undergo midlife crises, got me worked up. For starters, it brought home that Elder Millennials are in midlife. Checking the internet to comfort myself that I, a Juvenile Boomer, remain in midlife, I learned midlife crises can occur between 40 and 60, plus up to a decade on either end — most of our adult lives.

Series narrator Libby gets near the heart of her own crisis in the final episode when she asks, “It’s just, how can you live when you used to have unlimited choices, and you don’t have them anymore?” It’s Libby I identify with the most — Libby, living in the suburbs and supposed to be writing a book, who left her younger, hipper self behind in Manhattan, who had aspired to a creative life filled with cool adventure and professional recognition. Libby has lost something harder to wrangle in middle age than the sexual opportunity her friend Toby Fleishman finds online after his divorce.

In my parents’ generation, those who’d achieved a certain socioeconomic status were said to have “arrived.” All the main characters in “Fleishman is in Trouble” have arrived, but they are for various reasons unhappy, and Libby yearns to be back in life’s airport lounge holding an open-ended ticket in front of a blinking departure board.

One of the strengths of ”Fleishman” is the complexity with which it portrays aging in a society that offers up a helplessly snarled ball of contradictory expectations. Underlying the fear of aging is a fear of running out of time to untangle the mess and knit together the right strings to success. There is a potent fear of failure.

I’ve never forgotten a description of America’s obsession with youthfulness used by Clifton Fadiman in explaining why The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn could be considered the first great American novel. To Fadiman, centering a just-adolescent as the hero of the story reflected a central aspect of our culture: the “enskying of youth.” Youth is valued in many cultures, of course, not just this one, but that doesn’t make it any less a profound shaper of our perceptions and experience. The word “enskying” is what gets me. We don’t just value youth. We worship it.

In “Fleishman,” youth is potential, those “unlimited choices.” Libby checks herself, acknowledging that those things were neither all choices nor unlimited, but there’s the illusion: that everything is a choice and that we should never set or abide by limits, two imperatives that can make aging seem a fate worse than death. Our choices inevitably narrow. We’ve had to take one path over another “just as fair,” as Robert Frost poeted with frustrating ambiguity, “that has made all the difference.” Our limitations increase as our brains and our bodies begin to follow their arc away from the sky.

Excessive television watching has for years now fed me Progressive Insurance’s brilliant Dr. Rick commercials, wherein a self-help guru counsels adults who are “turning into their parents.” The humor is in the details, human behaviors chosen to tickle the reflex of recognition. The genius is in the tension, anxieties being tapped about aging. I enjoy the ads, watch each new one to see how perfect it is. The campaign’s vision of older people can’t be denied, however: They may be endearing, but the olds are fussy, meddling, judgmental, out of touch, tedious, predictable, embarrassing.

The desire to avoid being like your parents is fundamentally adolescent. Around Huck Finn’s age, children start to notice the many things about their parents that annoy and embarrass them. The humor in the Dr. Rick commercials relies on consumers of first-home-buying age (for the average American, their mid-30s) still feeling that teenage aversion. What keeps the ads from being too mean is the sense of inevitability: of course we will in some ways come to resemble our parents, (and here, look, the responsibility of buying a house and shopping for insurance is not so stodgy after all.) At the same time the ads reinforce the desire to forestall the full evolution as long as possible. Because ugh, parents.

Similar mixed messages come in on TikTok and Instagram through videos structured with a “You know you’re old when…” joke set-up. The algorithm fortunately keeps mostly delivering me ones by self-identified introverts, those who insist on the freedom to act like an older American or a Dane of any age and to pull on fluffy socks and stay in, cuddled up with popcorn and a movie. These are videos made by people much younger than I am, adults resisting FOMO and the suggestion that to be and stay youthful requires constant motion, ever striving to live, damn it, live! Sleep when you’re dead!

In this vein, two recent pieces on aging in The New York Times poked my inner Eeyore: one about Boomers and the Silent Generation having sex and the other about them having dance parties. Both seemed framed by surprise and packed with reassurance for the newspaper’s younger readers. Look! Older people still have sex! And older people still dance! Which, duh.

If, as we age, activities important to our well-being in our youth are still enjoyable and available, that’s a beautiful thing. Sex and dancing, though, happen to be physical activities tightly bound with ideas about youthful social desirability. So for older readers, there can be a discouraging subtext: worry about not being one of these hot, vivacious olds. Of course, everyone wants to stay healthy and enjoy life as they age. The Times’ “The Joys (and Challenges) of Sex After 70” is more problematic as it actively withholds any excuse not to pursue what it defines as a healthy sex life: not the emotional betrayals of life partners nor the physical constraints of illness or injury. Your cancer is no excuse not to overcome spousal infidelity and resolve childhood trauma to push sexual boundaries! Everything is a choice. We should never set or abide by limits.

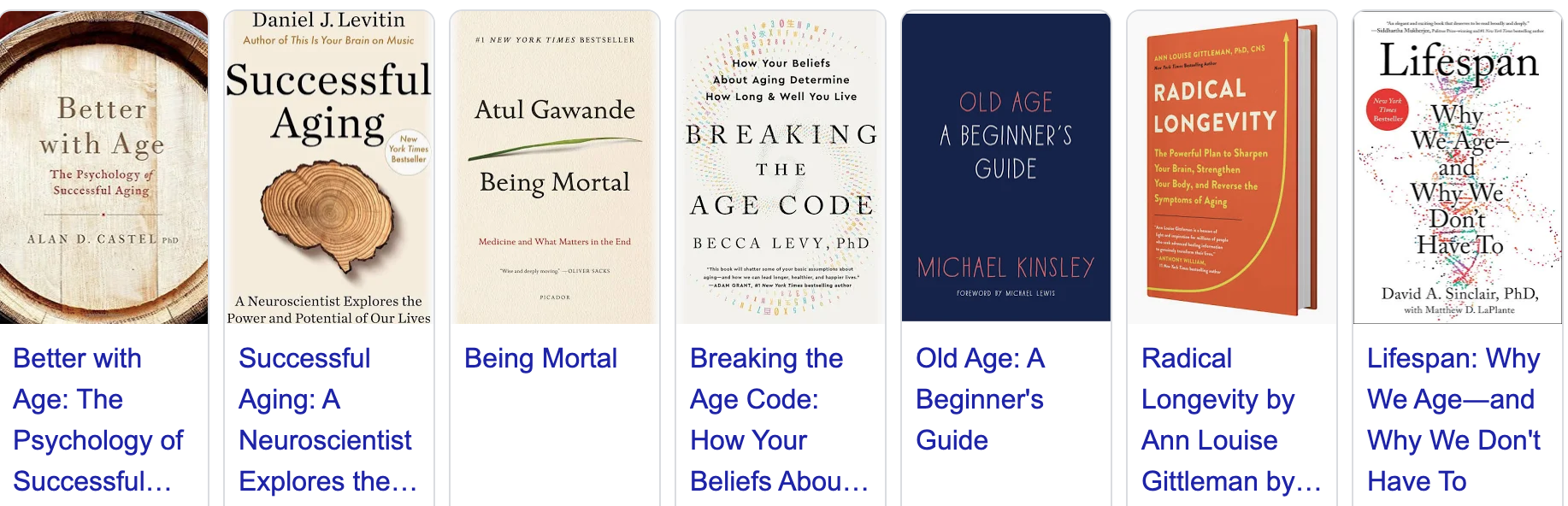

This insinuates, as so many books on aging seem to, that just as there were many ways to fail in school, young adulthood, and midlife, there are many ways to fail at old age. The titles of some of these books say it all: “Successful Aging: A Neuroscientist Explores the Power and Potential of Our Lives” to “Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging” to “Breaking the Age Code: How Your Beliefs About Aging Determine How Long and Well You Live.” Or how about this for denial? “Lifespan: Why We Age―and Why We Don't Have To.” I’m sure the advice within is less offensive, but the marketing sucks.

The midlife crises the “Fleishman” characters are having isn’t about their exact age, though mid-career pressures and the responsibilities of parenting young children loom large. They are about how they can’t be, won’t be young again. Of course then we can have a midlife crisis at any age. (Spend any time with high school seniors and you’ll see them mourning for their younger selves.) The resolution is in the acknowledgement of mortality, that humans do indeed have a lifespan, do age — and that this is not failure.

I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to reveal there is an affirming montage near the end of the final episode, a throwing off of cynicism, resentments, and fears. It is a jumbled series of snapshots — no before and after anti-aging commercial shoot — an appeal to embracing aging, to living in the moment, to the acceptance that allows us to capture joy in all its forms. It’s a call to ”unsnare time’s warp” and find ourselves in the daily, to be here and now.