Truth-Telling About Schools is Hard. Lying is Easy.

Alexandra Robbins’s “The Teachers” and writing about education

“You may think you know what’s inside, but you don’t.”

The first sentence of Alexandra Robbins’s “The Teachers: A Year Inside America’s Most Vulnerable, Important Profession” could also be its last. This isn’t a criticism of the book, which provides something rare and valuable: insight into the lives of teachers via someone who spent time with them and in their shoes, working in classrooms. It’s that no one book can provide more than a glimpse inside our schools.

It’s hard to get at the truth

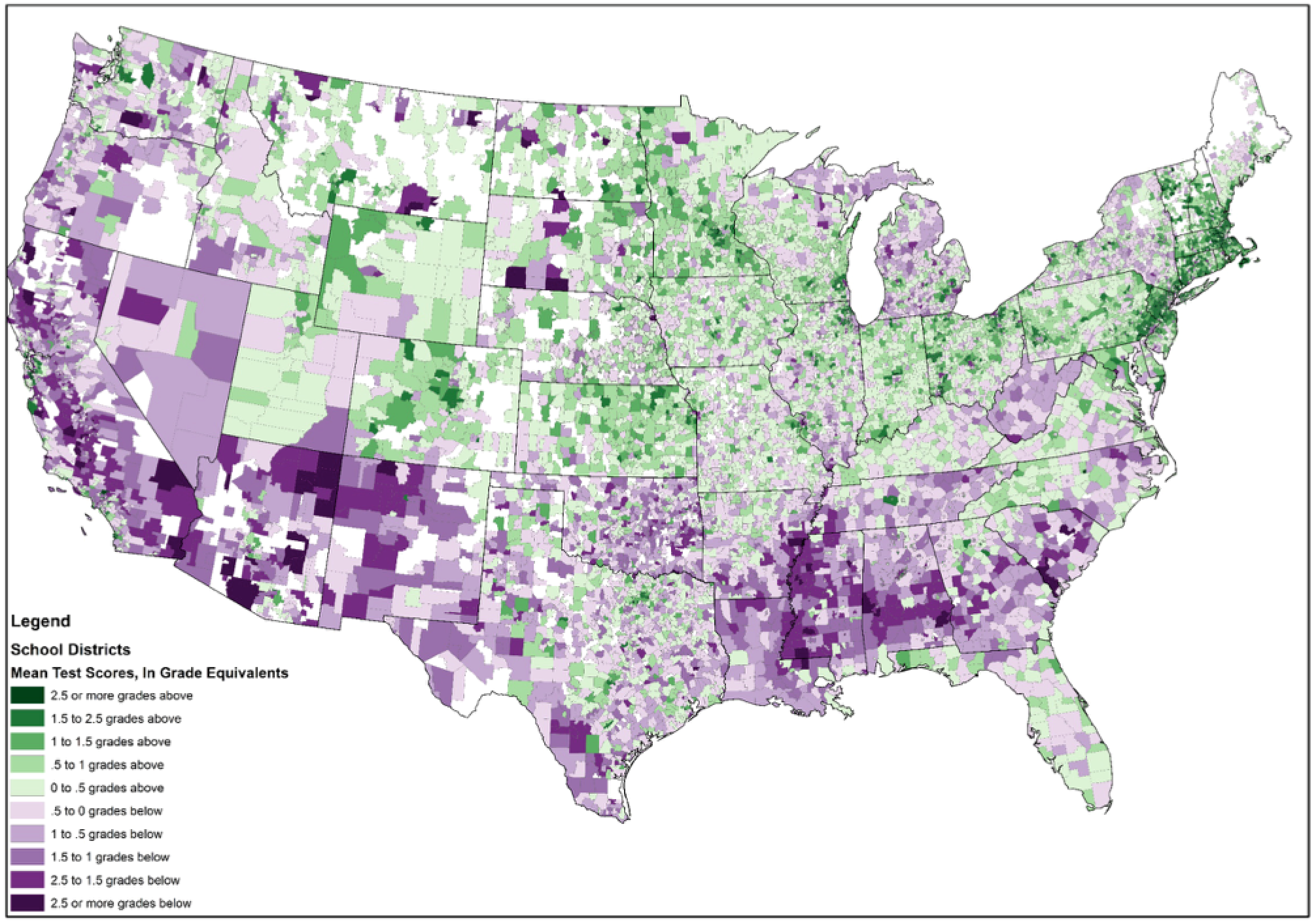

One reason why it’s difficult to write the full truth about education is the same reason it’s easy to broadcast lies about it: In a sense there is no such thing as “America’s schools.” What we have instead is a historically decentralized, astoundingly complex system of education evolving within an enormous, diverse, evolving nation.

This system educates children from early years to adulthood; from Maine to Maui; from city to suburb to country; from public to magnet to charter to independent to religious to home school; from enclaves of wealth to areas of historical disinvestment; from buildings with ten students to those with tens of thousands. Add variation in curriculum and instruction across subject areas decided by individual states, localities, or schools and under continual reform. Add differences in non-academic functions: transportation, food, healthcare, counseling, and library services, work-study, athletics, extracurriculars. Add the complications in how schools are funded. Add the vagaries of national, state, and local policy-making and politics. Add the complexities inherent in the processes of teaching and learning.

Hence the difficulty of discerning truth in education. Karin Chenoweth, author of “Districts that Succeed,” wrote to me:

“You can study state and district policies; you can talk to professors of education; you can go to conferences educators attend; you can read a lot of research; you can study different kinds of data; you can even visit a bunch of schools and classrooms in person. You can do all that and you might develop a general sense of some trends and tendencies, but that’s pretty much it.”

For her book, Robbins chose to delve deeply into the stories of just three teachers from different regions. Much can happen in one school year, so the three enable Robbins to cover a host of problems plaguing the profession and contributing to the “teacher shortage,” with a particular focus on overwork and on bullying, abuse, and violence. The book shows what happens to the empathy givers when empathy is withheld from them.

Reading it, I found myself increasingly anxious. I left teaching the summer before the 2021-2022 school year, but Robbins’s storytelling style returned me to the rooms where I experienced joy and satisfaction but also stress and struggle. Robbins toggles back and forth between the teachers’ tales, zooming in and out on the broader issues, a structure that contributed to my feeling overwhelmed. Context and interviews with additional educators showed these teachers’ experiences aren’t atypical — but it was a lot to absorb.

Having written about America’s teachers, I can hear the publisher’s likely prodding: “What’s the narrative arc?” The thing is that teaching and learning rarely has one. It’s usually a series of fits and starts, as “The Teachers” lays bare: students make progress and then backslide, initiatives are launched and abandoned even if they are effective, praise one day turns to hell-to-pay the next, and the year can close without closure. To tell the truth about schools rarely makes a tidy narrative. It demands the writer cover a lot of uneven ground— to do too much, just as many teachers are asked to do.

It’s easy to spread lies

At the same time, the complexities of our system make it easy for politicians, pundits, and profiteers to misrepresent it or lie about it. Parents, citizens, taxpayers all want to understand what is going on in schools, but individual districts are complex and the larger system mind-boggling. Simple messages sate that desire. Propagandists know the easier an idea is to understand, the more likely it is to be believed. Simpler messages are also easier to repeat, leading to an “illusory truth effect.”

The consistent, dominant, simple narrative on the right for decades now has been: America’s schools are failing (when there are great variations between and within regions, states, districts, and schools) because unions resist change and protect bad teachers (when union power from state to state ranges from strong to nonexistent, when stronger unions have been shown on average to lead to improved academic performance, and when controlling for SES, private schools have shown no advantage).

Fundamentally, little has changed when it comes to this narrative, though what is meant by “bad teachers” has slid quickly in recent years from bad (incompetent and lazy) to worse (indoctrinating and pedophilic). Pushing the smear that teachers are degenerate, “The New York Post” does its darnedest to collect and publish stories about educators engaged in wrongdoing and not just in New York City but across the country; if they can’t find any among the US’s 4 million teachers, they go overseas to keep up the pace.

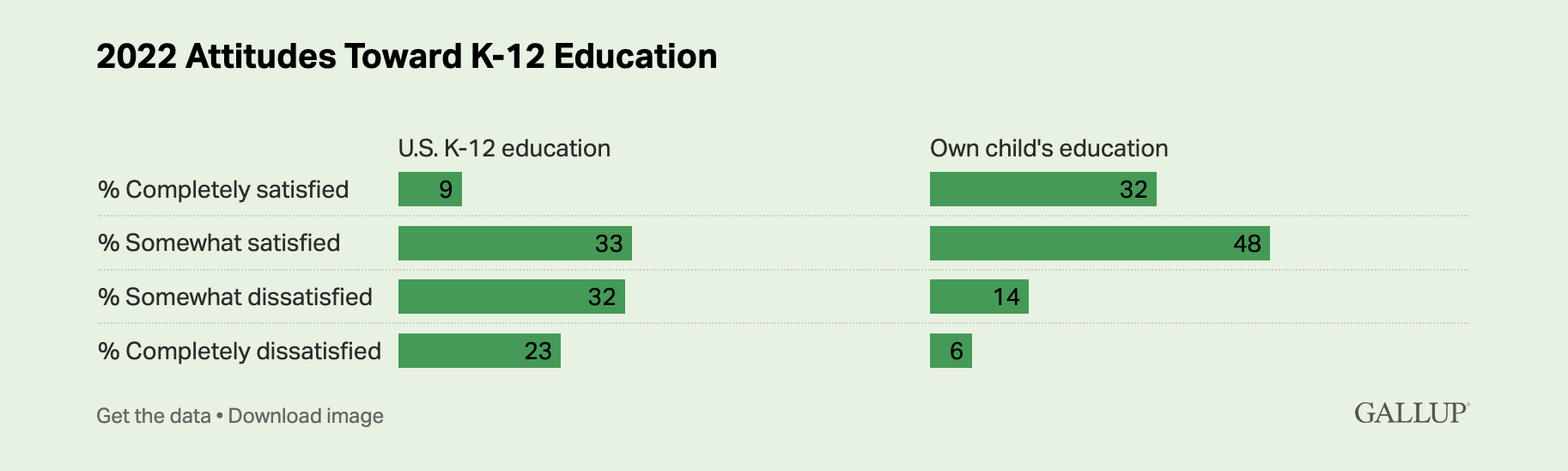

Familiarity breeds trust, which accounts for a recurring poll result that can seem confounding: most parents trust and view their own children’s schools positively but view the nation’s negatively. In other words, direct experience makes people familiar with and trusting of their own schools and teachers while their simultaneous media experience makes them familiar with narratives about and distrusting of the rest.

This explains the rise of unsupported claims that schools are hiding curriculum and more from parents. The right wants parents to disbelieve their own experience with schools by making the familiar strange and the comfortable suspect. It’s easy to say that schools are hiding things — it takes four words. It takes a lot more to explain the many ways in which schools are transparent and where and why we might want schools to provide more or less.

Claims of a lack of transparency give each anecdote a power boost. “Stunning numbers of opinion writers have drawn on the same anecdotes,” Karin Chenoweth explained, “to ‘prove’ their case that classrooms have become hotbeds of radical Marxism, harbingers of a totalitarian takeover of our schools. And it’s not just them—in “The Atlantic,” George Packer was allowed to make sweeping generalizations about what is taught throughout the country based on his kid’s rather eccentric school in Brooklyn. I mean, if something is true in one classroom then it’s true for the other millions of classrooms, right?”

So, a related reason it is hard to tell the truth about schools is that time and energy is drained trying to disprove falsehoods and argue against wild proposals: No, it’s not true that teachers are providing litter boxes for students who identify as cats. No, it’s not true that schools are full of radical teachers. No, arming educators won’t make students safer. And as Alexander Russo has complained, the conflict-rich stories that result from provocateurs’ lies and extremist legislation are diverting the attention of many education journalists from a range of meaningful issues.

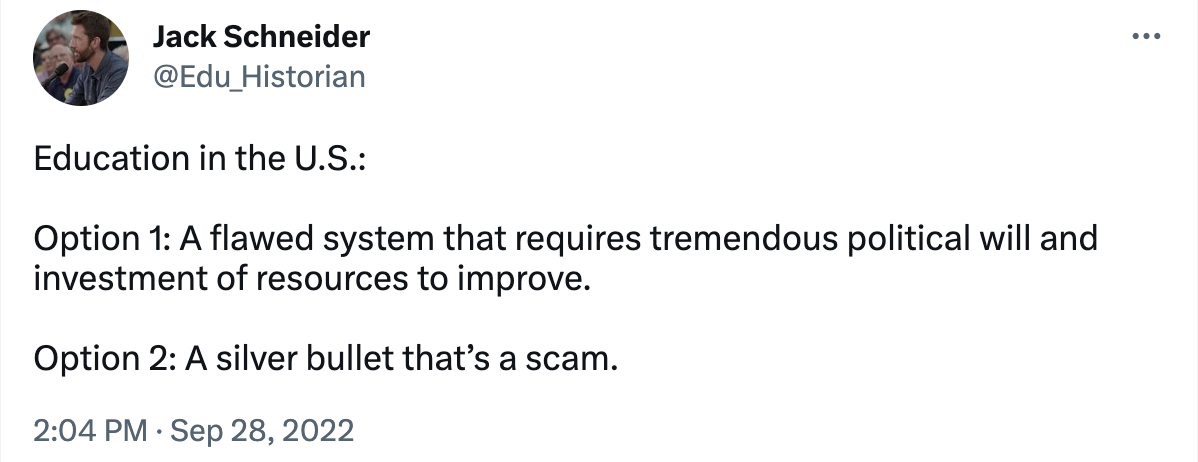

The beguiling beauty of simple problems is that they only require simple solutions. It’s easy to say tax dollars should follow the student — it’s been the mantra of privatizers for more than a decade. It’s easy to yell that the system should be trashed — that’s the sledgehammer of the openly anti-democratic. The answers that come from trying to truly understand our system are rarely simple and neat. It’s even easy to say that we should listen to teachers. Teachers will tell you about how much is out of their control (a great deal!), but they will also tell you what they know is effective in their particular communities with their particular students. Listening to them, as Robbins shows, requires a lot of work — and it is just part of the process of finding solutions, not a solution in itself.

It’s hard to identify and analyze the constellation of factors that produce better schools, to dig deep to pick up the common threads between successful districts. Chenoweth did that work. Good districts, she concludes, have much to teach the rest of them — and the rest of us — including “that the work is never done.” After decades of studying and reporting on education, she admits there is more for her to learn. Anyone with a hot take on schools who suggests otherwise may have something bridge-like in inventory.

Thanks for reading Nobody Wants This! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.