What We Talk About When We Talk About the Economy

And the problem with consumer and voter confidence

I’ve been obsessing about how much preserving our democracy through the 2024 election depends on voters’ views on economic issues, so I was drawn to Annie Lowrey’s new piece in The Atlantic about the disconnect between broad economic data and Americans’ sense of financial well-being.

She writes:

The gap between how the economy is and how people feel things are going is enormous, and arguably has never been bigger. A few well-analyzed factors seem to be at play, the dire-toned media environment and political polarization among them. To that list, I want to add one more: something I think of as the “Economic Annoyance Index.” Sometimes, people’s personal financial situations are just stressful—burdensome to manage and frustrating to think about—beyond what is happening in dollars-and-cents terms. And although economic growth is strong and unemployment is low, the Economic Annoyance Index is riding high.

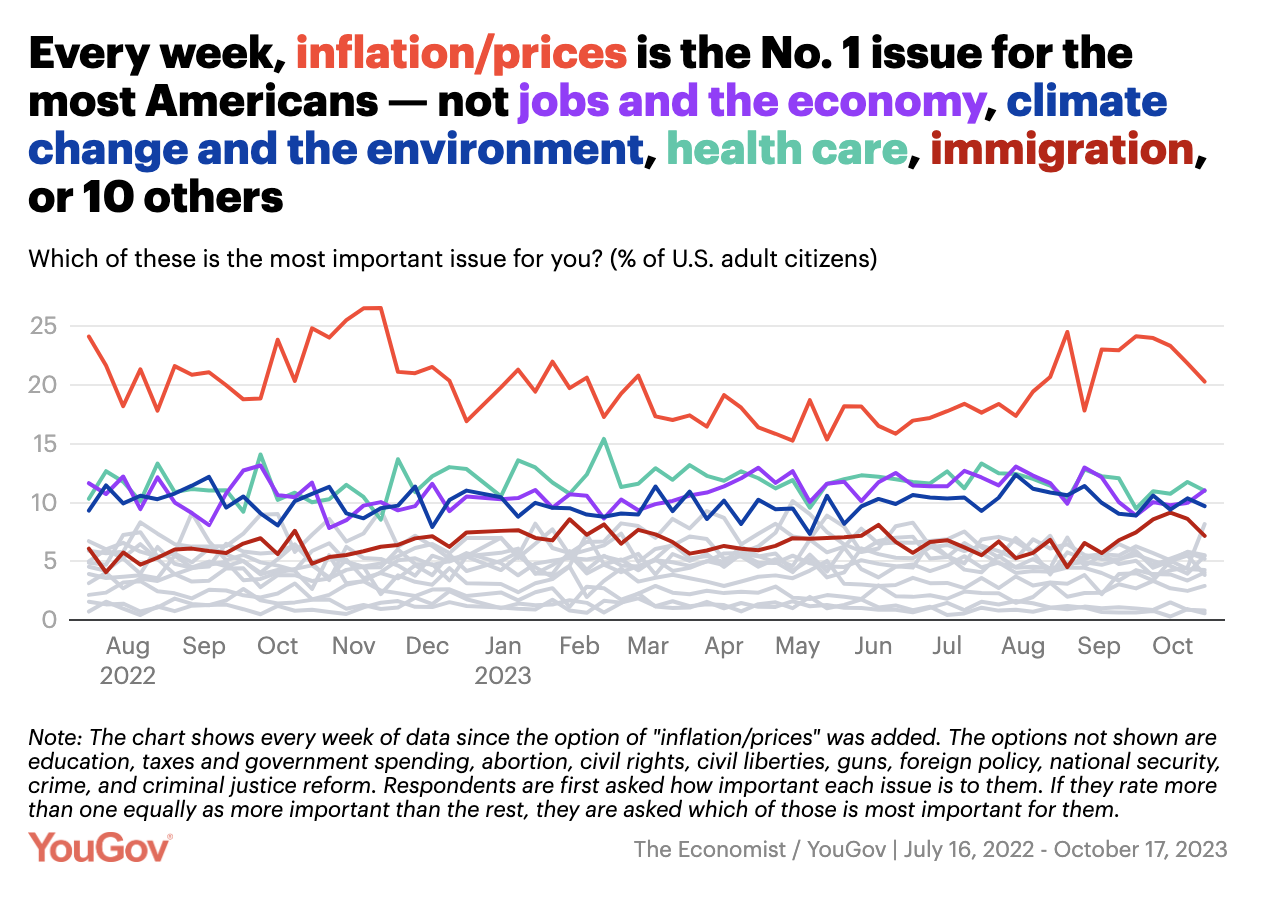

Lowrey devotes space to how politics, pessimistic media coverage, and nostalgia skew views, but she also shows how inflation (despite its downward trend) and high interest rates mean household budgets remain under serious pressure.

It’s insufficient to focus on employment and wage rates when many can’t find a house to buy or are weighed down with college debt, and another major household expense, transportation, is also dependent on loans. (Cars have long taken huge bites out of budgets, and that’s only gotten worse.)

Wages Aren’t Everything

The wage increases we’ve seen are cause for celebration. But they provide only part of the picture of most Americans’ financial health. Many work in fields where decades of low pay created gaps that cannot be spanned by a modest wage increase. More Americans work multiple jobs and have multiple bosses to please. More are gig workers and at-will workers, with the job insecurity that comes with that. Some have no control over their work schedule. Fewer than ever have defined benefit pension plans and because 401K plans have been a poor replacement, the typical American has just $144K in savings for retirement. Fewer receive health benefits. And even those workers who received modest wage or salary increases see top management and shareholders basketing an increasing share of the fruits of their labor.

Wage increases help families. But modest increases can only do so much in the face of decades-long structural forces that have pummeled worker compensation, job security, and retirement security. It’s hard for Americans to earn the money needed to be and feel financially safe and secure.

Consuming Frustration

Even for those with money to spend, being a consumer is harder than it should be. When I first saw the headline to Lowrey’s piece, “The Annoyance Economy: Data alone don’t capture how frustrating and stressful it is to be a consumer right now,” a list of aggravations sprang to mind. In an Economic Annoyance Index, I would include factors that make being a consumer more painful than it was in the past. It can feel like work, a roiling undercurrent to consumer sentiment. Here are some:

Shortages: Finding or affording needed products can be difficult. Industry overconcentration after decades of lax antitrust enforcement can create shortages. The baby formula shortage last year underscored how dangerous this is. Pharmaceutical mergers can contribute to drug shortages.

“Shrinkflation”: Brand manufacturers have been downsizing products, giving consumers less for their money. It’s not just processed foods, snacks, and candy; it’s also basics such as toilet paper and detergent.

Crappier products: Clothes are a good example here, as the fashion industry trained consumers to trade out clothes more often, but it hasn’t been alone in lowering quality to increase volume. Products break and wear out more easily, making them disposable instead of repairable, which means more time, energy, and money spent replacing them—with something that may be yet worse.

Tipping and checking: In US restaurants and hotels, tipping is a long-standing custom (with its roots in slavery) that allows employers to avoid paying a living wage. Electronic tipping suggestions by more kinds of businesses for more jobs can cause angst or resentment. Consumers are bombarded with surveys demanding they evaluate someone else’s employees.

Extra steps to returns: High return rates, a problem partly of companies’ own making (see “Crappier products” above), have led retailers and e-commerce firms to institute less generous, more onerous returns policies.

Less-than-human customer service: Dealing with automated phone systems or chats can range from off-putting to enraging. People want help from people, and it often takes too long for customers to get to that point.

Locked shelves and closed stores: Some retailers are responding to shoplifting by locking up more goods (though inventory shrinkage is built into forecasts), creating inconvenience and stoking fear. Target blamed crime for store closures that would require consumers to travel farther to shop, though Judd Legum’s analysis showed crime was not higher but lower in the locations slated for closure.

Hidden and junk fees: Searching for airfares, hotels, and other services online can be grossly misleading as a result of hidden fees that aren’t tacked on until the last minute and that may have no real value (a resort fee at a city hotel that has no resort amenities, for example).

Auto-pay: Auto-pay and auto-renewal can make it easier to be a consumer, but it can also make it harder due to the intentional creation of obstacles to canceling subscriptions or closing accounts with recurring charges. I call this capitalism by attrition. Cable upgrades, for example, are available with one click on TV or website, but a downgrade can require hunting down a customer service number, calling during limited hours, waiting to be called back, and fending off aggressive sales pitches.

Some of these consumer annoyances are small, and some are large, but they add up to real, higher costs for families and a persistent sense that there are no good deals, only raw ones, that there is no fair play, just advantage being taken. (See more in the newsletter by Nate Bowling that arrived in my inbox as I was writing this.)

When We Talk About the Economy

The Biden Administration seems to understand that corporate power is overwhelming workers and consumers. Though he can do more, Biden has been vocal in support of unions, making his support for the striking automakers visible by joining them on the picket line. His FTC has been fighting for some consumer rights: new rules have been proposed to make cancelling subscriptions easier (the “click-to-cancel rule”) and to eliminate hidden and junk fees, for example. A few weeks ago it launched a lawsuit against Amazon for its “ongoing pattern of illegal conduct blocks competition, allowing it to wield monopoly power to inflate prices, degrade quality, and stifle innovation for consumers and businesses.” Other antitrust cases are underway.

How Democrats can help voters see they are the party interested in their ability to get more and spend less is a question for political experts. Those of us who do some of our political work by talking with friends, family, colleagues, and neighbors know it’s not enough to note that prices are falling or wages have risen. Fortunately, by working in various ways to counter excessive corporate power, the current administration is giving us something meaningful to talk about.